Types of cross country skiing

Cross country skiing has been described as “a relationship between man, equipment, and environment.” Jim Gaffigan, a popular comedian, discriminates between downhill and cross country skiing this way: “You know that awkward thing you do to get to the chair lift? That’s cross country skiing.”

Not exactly.

While cross country skiing involves human powered locomotion across flats AND both UP hills as well as down them, it is better summarized as a marriage of science, art, and braun. There is the chemistry of snow science and its mysterious relationship with wax, base materials, ski flex, and grinds. There is the technical and physical mastery numerous quadrupedal movement patterns which comprise all of essential sub-techniques, which, when done correctly, place the skier in a happy ‘floating’ state of mesmerization as they effortlessly coast through woods, over hills, and across valleys. Alas, to some degree, a skier must have some level of strength and toughness, too. .

Hopefully, all of that waxing of poetic nostlagia did not frighten you away. After all, if you are reading this, you are likely a newcomer to the sport. Greetings! I’m glad you are here! The best part about cross country skiing is its accessibility to all ages and abilities. Sure, like anything, it can be as complex as you want it to be. But if all you are looking for is a way to be outside, kill a few calories, and find an alternative to walking the dog along the iced over sidewalk on cold winter mornings, then you’ve come to the right place.

The next question you might be having is:

What is cross country skiing?

Cross country skiing exists in two techniques: classic skiing and skate skiing.

Each technique has four sub-techniques, or movement patterns, that correspond to speed and terrain. Let’s take a look at the four sub-techniques for classic skiing:

Classic Diagonal Stride

With weight over one foot, the skier ‘sets’ the wax pocket with a downward force impulse. This allows the grip wax on that ski to grab onto the snow for a very brief time. This traction allows the skier to push off and swing his opposite leg through, underneath the hips, and onto the snow, where it starts the glide phase. The skier transfers his weight to the gliding ski as it moves underneath his body before repeating the same process on that ski. Diagonal striding is about “kicking” and “gliding.”

This is the oldest movement pattern for skiing, and the level of dynamic movement is contingent upon the ability and strength of the skier. You can start by simply walking and progress to very dynamic force impulses, which are required for steeper uphills at high speeds.

Typically, this pattern is for gradual or steep uphills, but is also enjoyable along flat terrain as well.

Classic Double Pole

The double pole is the most fundamental movement pattern in all of cross country skiing, as the body position and movement patterns are at the heart of skate skiing and classic skiing. Mastering it is crucial for this reason, and also because the upper body strength/endurance required to double pole (DP) for long periods is essential for higher level racing.

The double pole consists of simultaneous engagement of both poles with the ground in powerful force impulses. If the skier has a correct forward lean and stable core, the weight of the skier falling on the poles acts as the main source of power. From the side view, when the poles make contact with the snow, the skier appears to be in a “plank” position. Upon the follow through, the skier must reposition his center of mass at a high position quickly (especially if he is going uphill!) to repeat the process, making this movement a much more ‘total body workout’ than you might have initially envisioned.

This is performed on the flats or uphills, depending on the strength and technique of the athlete. In the pro ranks, today’s skiers utilize this technique at a much higher frequency than 30-40 years ago, much to the chagrin of many ‘purists.’

Classic Kick Double Pole

The kick double pole is an intermediary sub-technique which is used on flats and gradual uphills when diagonal striding is too slow but straight double poling is too difficult. At the highest level, skier’s rarely use this technique (at least post 2018), but it is a nice feature to have in your toolbox on long days when you want to mix things up.

Essentially, this is a combination of applying grip wax to a single ski and using the double pole motion. It is difficult to conceive of by reading, and I would suggest watching a video of it in motion (you should do this for all of the techniques!) to have a conceptual target to shoot for as you practice.

Classic Herringbone

On steep uphills, you will sometimes need to use the herringbone technique. The movement pattern is natural, like striding, except the skis are placed at angles so that the edges of the skis can be used to grip the snow. Often, if the grip wax has failed, skiers will resort to herringboning up hills which they would prefer to be striding!

This technique is tricky to do well, I think, as it is a lot like trying to run….with 205cm planks attached to your shoes. Don’t be embarrassed if you can’t do this really fast right away…or if you trip while practicing it!

All Classic Techniques

How do you know which sub-technique you should be using? Well, each sub-technique, or ‘gear’ is used in a similar fashion to the gears on a bike. They have to do with speed. Like cycling, your speed is often parallel to the terrain, but not always. For example, you might have very slow conditions, requiring you to stride where you otherwise would prefer to double pole. Or, you may approach a very steep grade where herringbone is typically required, but since you approached it coming off of a fast downhill, you can maintain momentum and simply double pole over it. So, I like to think of my gear choice in relation to both speed and incline. This graph shows each of the mentioned sub-techniques along a speed continuum.

The other type of cross country skiing is the skate, or freestyle technique. This technique first surfaced in the early 80s, and it was deftly developed and utilized by a creative American named Bill Koch (link to article on “Skiers that every Nordic fan should know”) to win the overall World Cup title in 1982. Afterwards, everybody started using the skate and marathon skate technique, and it appeared as though the historic traditional classic stride was about to die. This led the International Ski Federation (FIS) to, in 1983, split ski events into the two categories we have today: freestyle and classic. In classic races, freestyle techniques are prohibited.

Just to give you a basic conceptual image for your mind, I’m going to simplify freestyle skiing to this: the lower body is doing a skating motion (like hockey or rollerblading), and the upper body is double poling. Serious coaches and athletes are probably angry with me for saying that, but I think it will help you as read my attempt to write about movement patterns…which is not easy….

Let’s take a look at the sub-techniques within the freestyle technique:

Freestyle V2

In the V2, or one skate, a pole push occurs on every skate push. The skier still has a weight shift (this is something beginners struggle with) from ski to ski. While gliding, a skier is over the top of the glide ski, with their center of mass at a high position straight over the ski. The poles are prepped to engage with the ground, hands at eye level. At the moment of force impulse, the skier engages the upperbody in the same manner as he would with the double pole, and the lower body kicks down on the ski simultaneously. This is the marked difference with skate skiing and ice skating. In skate skiing, the lower body makes the force impulse with the weight of the skier more vertically/over the top of the foot, whereas in skating, you are pushing off to the side. In skiing, this vertical placement is critical because of the unification of the double pole motion with the lower body ‘kick.’ After the force impulse, the skier shifts his weight to the gliding ski (the opposite ski), raises his center of mass over that ski, and repeats the motion.

Freestyle V2 alternate

In the V2 alternate, or two-skate, a pole push occurs on every OTHER skate push. The skier dynamically swings his arms on the other skate push to aid in momentum. While the V2 is used for gradual uphills or flats, the V2 alternate is used when ski speed becomes too fast for V2 to be useful – so, high speed flats or gradual downhills, normally.

Freestyle V1

V1, or offset, is the climbing gear for skate skiing. You will see this on steeper uphills, or, if one is out of shape, gradual uphills or even flats (sorry, out of shape people….we can now identify you….)

Poles and skis do not hit the ground all together. Describing this movement pattern is quite difficult, and I’m not going to attempt it. There are plenty of helpful youtube videos out there which slow it down for you. I needed to watch them several times to see the timing of each ski and pole as it makes contact with the ground. I suggest doing that and then practicing with and without poles until you get the hang of it. It’s a bit like riding a bike ….once you can do this, you won’t think much about it…but until then, it feels kind of awkward.

Freestyle Free Skate

The free skate is where a skating motion is used without poles. This happens on very fast downhills, when the speed is so great, it does you no good to engage your poles. Think of cycling down a hill at 55 mph….would it help to pedal? Not unless you can do 190 RPMs….

Skier’s engaged in this technique will swing their arms and get into an aerodynamic crouch. Probably no World Cup skier is better at a ‘working downhill’ using this sub-technique than Jess Diggins.

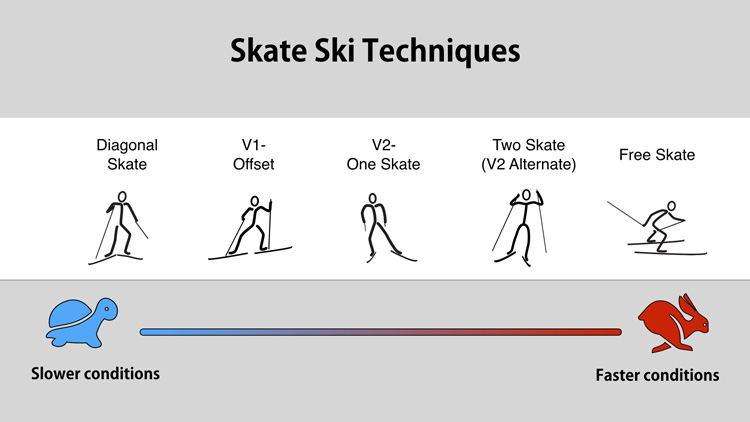

Freestyle All Techniques

By speed…..

Freestyle All Techniques

by terrain/grade